A History of the Real

LEGIO IX HISPANA

(Legio VIIII Hispana)

Edited and compiled by Rob Zienta

Legio IX or Legio VIIII, which is correct? Actually, both are correct. Tiles have been found stamped with either designation, indicating the Legion was identified either way. Regardless, the Ninth was one of Rome's venerated legions and its disappearance, which is shrouded in mystery, has captured the imagination of authors and film makers? No one knows for sure why, but sometime after 108/9 AD, the legion all but disappeared from historical records.

The

popular version of events — propagated by numerous books, television programs and films — is that the Ninth,

at the time possibly numbering some 4,000 men, was sent to vanquish the Picts of modern day Scotland and

marched mysteriously into oblivion, never to return. Of course, no good storyteller would ever let something

trivial like facts get in the way of a good story and the legend of Legio IX Hispana's mysterious

destruction, possibly at the hands of Scots savages, is certainly a gripping tale. Little surprise then the

story continues to be retold in novels and on the big and small screen. Red Shift

by Alan Garner, Engine City by Ken MacLeod, Warriors

of Alavna by N. M. Browne, Legion From the Shadows by Karl

Edward Wagner and La IX Legione by Giorgio Cafasso are just a few of the many

books that touch on the legendary destruction of the Ninth in some way. The most famous novel to deal with

the legion's story — The Eagle of the Ninth by Rosemary Sutcliff, published in

1954 — is one of the most celebrated of the 20th century, selling over a million copies worldwide. A BBC TV

serial of the book was aired in 1977 and a recent film called The Eagle of the

Ninth, or The Eagle, as it is also known,

was based on Sutcliff's book.

The

popular version of events — propagated by numerous books, television programs and films — is that the Ninth,

at the time possibly numbering some 4,000 men, was sent to vanquish the Picts of modern day Scotland and

marched mysteriously into oblivion, never to return. Of course, no good storyteller would ever let something

trivial like facts get in the way of a good story and the legend of Legio IX Hispana's mysterious

destruction, possibly at the hands of Scots savages, is certainly a gripping tale. Little surprise then the

story continues to be retold in novels and on the big and small screen. Red Shift

by Alan Garner, Engine City by Ken MacLeod, Warriors

of Alavna by N. M. Browne, Legion From the Shadows by Karl

Edward Wagner and La IX Legione by Giorgio Cafasso are just a few of the many

books that touch on the legendary destruction of the Ninth in some way. The most famous novel to deal with

the legion's story — The Eagle of the Ninth by Rosemary Sutcliff, published in

1954 — is one of the most celebrated of the 20th century, selling over a million copies worldwide. A BBC TV

serial of the book was aired in 1977 and a recent film called The Eagle of the

Ninth, or The Eagle, as it is also known,

was based on Sutcliff's book.

With such a mythology evolved around the Ninth's disappearance it's difficult to separate fact from fiction. The real explanation of the "lost legion" may very likely be much less simpler and mundane than "the myth" — in reality, the unit may have simply been disbanded, as it had been several times before, continued to serve elsewhere, or finally destroyed at another battle some years later. The myth, as is so often the case, tends to overshadow the truth. We present here our unit's story based on what we have found in historical reference and archaeological evidence.

The Beginning

Along with Legios VII, VIII and X, Leg. IX Hispana (The "Spanish Legion") —

was one of the oldest and most feared units in the Roman army. Raised by Pompey

in 65 BC, it fought victorious campaigns across the Empire, from Gaul to Africa, Sicily to Spain and Germania to Britain.

Along with Legios VII, VIII and X, Leg. IX Hispana (The "Spanish Legion") —

was one of the oldest and most feared units in the Roman army. Raised by Pompey

in 65 BC, it fought victorious campaigns across the Empire, from Gaul to Africa, Sicily to Spain and Germania to Britain.

The Legion first came under the command of Julius Caesar, then the Governor of Further Spain in 61 BC. Expert at

inspiring loyalty in his troops, he found one of his most devoted veteran armies in the Ninth. Although no

record of the Legion's emblem exists, like all of Caesar's faithful legions, it was probably a bull.

Therefore, we have adopted the bull as the emblem for our unit.

The Legion first came under the command of Julius Caesar, then the Governor of Further Spain in 61 BC. Expert at

inspiring loyalty in his troops, he found one of his most devoted veteran armies in the Ninth. Although no

record of the Legion's emblem exists, like all of Caesar's faithful legions, it was probably a bull.

Therefore, we have adopted the bull as the emblem for our unit.

The Ninth served with Julius Caesar when he invaded Gaul in 58 BC — the Roman commander mentions Legio IX in his accounts of the battle against the Nervians — and fought with him throughout the Gallic Wars from 58-51 BC.

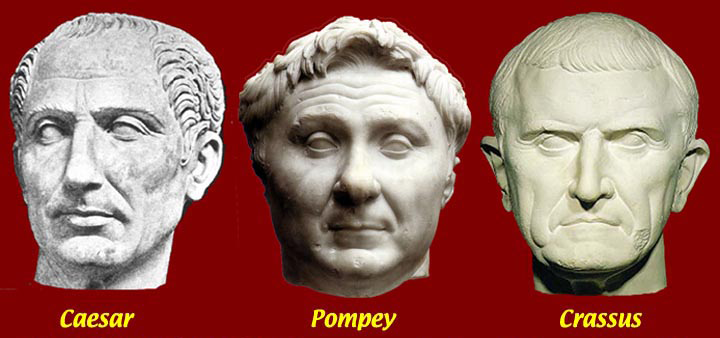

The Republic

The First Triumvirate of Rome included Julius Caesar, Pompey, and Crassus, with Caesar's election as consul, in 59 BC. It was an unofficial political alliance between Pompey's military might, Caesar's political influence, and Crassus' money. The alliance was further consolidated by Pompey's marriage to Julia, daughter of Caesar, in 59 BC.

In 52 BC, at the First Triumvirate's end, the Roman Senate supported Pompey as sole consul; meanwhile, Caesar had become a military hero and champion of the people. Knowing he hoped to become consul when his governorship expired, the Senate was politically fearful of him and ordered his resignation of command of his army. In December of 50 BC, Caesar wrote to the Senate agreeing to resign his military command if Pompey followed suit. Offended, the Senate demanded he immediately disband his army, or be declared an enemy of the people. They threatened Caesar with numerous potential prosecutions based upon alleged financial irregularities during his consulship. In addition, they threatened investigations and prosecutions for supposed war crimes committed during his Gallic campaigns and forbade his standing for election in absentia for a second consulship. Caesar loyalists, the tribunes Mark Antony and >Quintus Cassius Longinus, vetoed the bill, and were quickly expelled from the Senate. They joined Caesar, who had assembled his army in anticipation of the Senate's actions.

Because Caesar suspected he would be prosecuted and rendered politically marginal if he returned to Rome without consular immunity or his army, he did not comply with the Senate's demands; which prompted Pompey to accuse him of insubordination and treason and the Senate to call for his arrest.

Civil War

A Civil War (49-48 BC) erupted against Caesar, the Senate and Pompey, Caesar's fellow triumvir and rival. The Ninth fought with Caesar in Spain in the battle of Ilerda (summer of 49 BC) and later was transferred to Placentia (Piacenza, Italy) to quell a brief revolt.

In the spring of 48 BC, the Legion served at Dyrrhachium (near present day Durrës in Albania). The Ninth was also present at the battle of Pharsalus (a city in southern Thessaly, in Greece) and played a key role in Caesar's Victory (August 48 BC), which ensured his ultimate grip on the Republic. After this battle, the soldiers were again sent back to Italy to be pensioned off. However, in 46 BC they were reenlisted to participate in Caesar's African campaign.

After his ultimate triumph at the Battle of Thapsus, Caesar repaid the Ninth's loyalty and service by again pensioning off the men, disbanding the legion. Some veterans were settled in Picenum (the northern Adriatic coastal plain of ancient Italy), others at Histria (near Istros, on the shore of the Romanian Black Sea).

A Legionnaire's Work is Never Done!

The Ninth's service didn't end there, however.

After Caesar's assassination in 44 BC, the Legion was recalled in 41 BC by his adopted son Octavian,

who needed the Legion to put an end to Sextus Pompeius' occupation of Sicily that threatened the grain supply of Rome.

The Ninth's service didn't end there, however.

After Caesar's assassination in 44 BC, the Legion was recalled in 41 BC by his adopted son Octavian,

who needed the Legion to put an end to Sextus Pompeius' occupation of Sicily that threatened the grain supply of Rome.

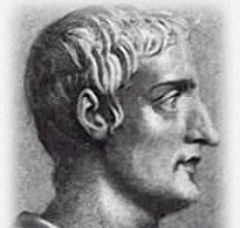

Left: Octavian (later, Augustus)

The Ninth was then sent to the Balkans, where it received the honorific title "Macedonica." An inscription referring to Legio IX with the title "Triumphalis" may prove the Ninth was re-founded even earlier and fought at Philippi in 42 BC. Victory took until 36 BC; which is when the Legion would have been stationed in Macedonia.

In an effort to consolidate his power as Emperor of Rome, Octavian launched the Ninth into another campaign, which was to be the final war of the Roman Republic. Octavian faced off against Mark Anthony and Cleopatra, eventually defeating them at the Battle of Actium in 31 BC, which established Octavian as the sole ruler of the Mediterranean with the name "Augustus" granted to him by the Senate in 27 BC.

The Ninth was next posted to Hispania Tarraconensis (Spain), where it fought with distinction in Augustus' long campaign against the Cantabrians from 25-13 BC. The campaign also included the legions I Germanica, II Augusta, IIII Macedonica, V Alaudae, VI Victrix, X Gemina, XX Valeria Victrix, and perhaps VIII Augusta.

The Ninth seems to have especially distinguished itself during the campaign of 24 BC, which may well have been where it received its honorific title "Hispana" or "Hispaniensis." The success of this campaign eventually ensured Roman dominance in the region.

It's unclear whether or not sub-units of the Ninth were transferred to the Rhine in 20 BC and active during Agrippa's invasion of Germania in the following year. Part of the confusion is an inscription that mentions a soldier of VIIII Hisp[ana] in Pannonia (an area lying roughly within the boundaries of modern Hungary) during the reign of Augustus, therefore, it is possible that the Legion was not stationed on the Rhine at all, but instead on the Danube or in Aquileia (today one of the main archaeological sites in Northern Italy). However, if the Ninth was transferred to the Rhine, it's likely to have played a role during Drusus' campaigns on the east bank of the Rhine.

A Definite Time and Place

In the confused months after the Roman defeat in the Teutobergerwald (Teutoburg Forest) in September of 9 AD, Legio IX was at Pannonia, which is confirmed by sources firmly placing the Ninth in the region in 14 AD, the year of Augustus' death.

The Ninth was permanently garrisoned in the city of Siscia (modern-day Sisak) on the confluence of the rivers Colapis (Kulpa) and Savus (Sava), until 43 AD. The only known exception, is in 21-24, when subunits of IX Hispana commanded by Publius Cornelius Scipio, were sent to Africa and Mauretania to support III Augusta in its struggle against the tribal warriors of Tacfarinas, a Numidian deserter from the Roman army who led his own Musulamii tribe and a loose coalition of other Ancient Libyan tribe in a war against the Romans in North Africa during the rule of emperor Tiberius (AD 14-37).

Invasion of Britain

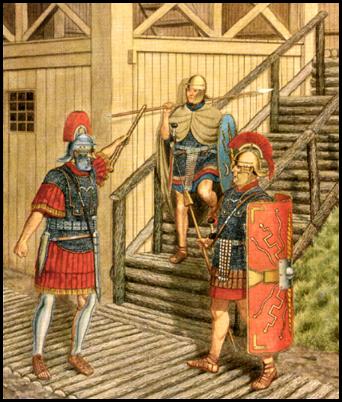

In 43 AD, the emperor Claudius invaded Britain. The Roman historian Dio writes the only known contemporary account of the invasion. While he does not name the Legions involved in the fight, from evidence of later years, we now know the numbers and names of these Legions: II Augusta, IX Hispana, XIV Gemina and XX Valeria Victrix.

Legio

IX was commanded by Aulus Plautius and would have only been a part of this massive invasion force.

The Ninth numbered 5500 men, not including the auxiliaries who were attached to the Legion. The Auxila would

have numbered approximately 5000, which meant the commander of Legio IX probably had 10,000 men under his

command.

Legio

IX was commanded by Aulus Plautius and would have only been a part of this massive invasion force.

The Ninth numbered 5500 men, not including the auxiliaries who were attached to the Legion. The Auxila would

have numbered approximately 5000, which meant the commander of Legio IX probably had 10,000 men under his

command.

From the Channel coast near Richborough, the Ninth is thought to have advanced northeastwards into the Norfolk-Suffolk area. If so, the Legion would have had to have crossed the Medway River. It's possible that at this time Legio IX was still in the company of Legions XIV and XX. During this river crossing the Romans met strong resistance by a native army under the joint command of Caratacus and Togodumnus.

The historian Dio tells us the battle was fierce and lasted two days. Caratacus escaped the Roman onslaught, and fled to Wales. Having crossed the Medway River, Legio IX probably advanced up into the friendly territory of the Iceni, in Norfolk, a client Kingdom under the rule of King Prasutagus.

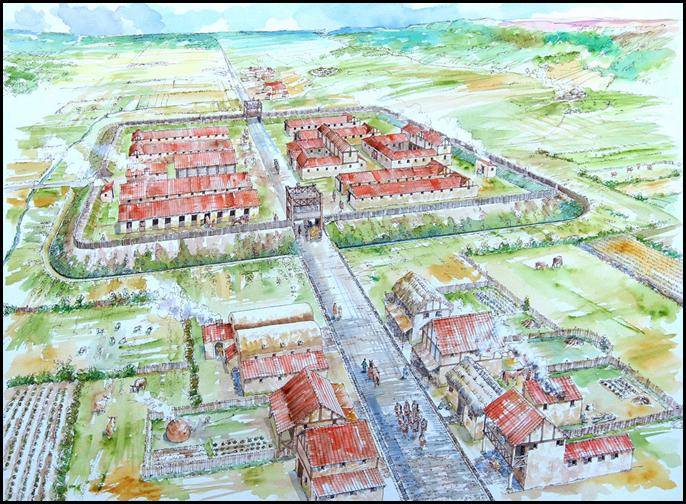

Archaeological evidence of Legio IX does not appear until it moved to a fortress at Lindum (Lincoln) in about 66 AD. Prior to this the two strongest possibilities for the unit's bases was Longthorpe in Cambridgeshire (near modern-day Peterborough) and the second at Newton-on-Trent in Nottinghamshire. These two sites were vexillation fortresses (a term applied to large Roman forts which were occupied on a temporary basis by campaigning forces), which suggest that Legio IX may have been split into several small units. It is probable that the tribes of Eastern England had not yet been totally pacified, and as such, needed constant monitoring by the Roman Military, which would explain why Legio IX may have been split. These vexillation fortresses were occupied until about 66 AD when Legio IX moved farther North. However, before this move, the Legion and the Roman Province suffered a drastic set back.

Boudicca's Revolt — A Woman Wronged

When

Claudius invaded Britain, the king of the

Iceni, Prasutagus, offered no opposition. A common practice

by the Romans was to offer such pro-Roman rulers the status of a 'client kingdom or state'. The Romans

benefited from this arrangement by avoiding the expense of garrisoning the territory; the 'client king'

(or, indeed, queen) kept the peace, and was assured wealth and Roman

backing against rivals. The contract was between Rome and the individual ruler, so when a king died, the

agreement died with him, unless he had a male heir, because women could not inherit property according to

Roman law.

When

Claudius invaded Britain, the king of the

Iceni, Prasutagus, offered no opposition. A common practice

by the Romans was to offer such pro-Roman rulers the status of a 'client kingdom or state'. The Romans

benefited from this arrangement by avoiding the expense of garrisoning the territory; the 'client king'

(or, indeed, queen) kept the peace, and was assured wealth and Roman

backing against rivals. The contract was between Rome and the individual ruler, so when a king died, the

agreement died with him, unless he had a male heir, because women could not inherit property according to

Roman law.

Only the names of three British client rulers are known, although there may well have been others. The three are: Queen Cartimandua, of the Brigantes, ruling most of (what is now) northern England; King Togidubnus, south of the middle Thames; and King Prasutagus, of the Iceni, in today's East Anglia.

In 60 AD, Prasutagus died without leaving a male heir. In an effort to secure the future of his kingdom, Prasutagus had named Boudicca, his queen, two daughters and the Roman Emperor as co-heirs, which was a common practice for rulers without an apparent male heir. However, corrupt Roman officials, procurator Catus Decianus and Senecca the Younger, were quick to use Prasutagus' lack of a male heir for their own benefit by invoking Roman law concerning the inheritance of property. They promptly laid claim to Prasutagus' property and possessions and demanded the Roman army enforce the law. Tacitus particularly singles out Catus Decianus for criticism for his "avarice."

According to Dio Cassius:

An excuse for the war was found in the confiscation of the sums of money that Claudius had given to the

foremost Britons; for these sums, as Catus Decianus, the procurator [finance official] of the island,

maintained, was to be paid back. This was one reason for the uprising; another was found in the fact

that Seneca [the Younger], in the hope of receiving a good rate of interest, had lent to the

islanders 40,000,000 sesterces that they did not want, and had afterwards called in this loan all at

once and had resorted to severe measures in exacting it.

(Dio Cassius, Romaika, 62.2.1)

The assets of the Iceni were seized by the army and the kingdom pillaged, Prasutagus' household enslaved as though they had been prizes of war, Queen Boudicca subjected to the lash and her two daughters violated. In addition, the Icenian nobility were stripped of their family estates and the relatives of the former king treated as slaves.

Incensed by this outrage and the dread of worse to come — because they had now been reduced to the status of a province — Boudicca and the Iceni rebelled and incited the Trinovantes and other tribes to join them. At the time of the rebellion, the majority of the Roman army in Britain was away on campaign in Wales, under the command of Governor Gaius Suetonius Paullinus, against a Druid stronghold of resistance on the island of Mona (Anglesey).

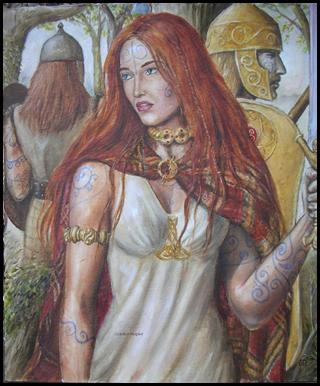

Dio continues:

But the person who was chiefly instrumental in rousing the natives and persuading them to fight

the Romans, the person who was thought worthy to be their leader and who directed the conduct

of the entire war, was Boudicca, a Briton woman of the royal family and possessed

of greater intelligence than often belongs to women. This woman assembled her army, to the number

of some 120,000, and then ascended a tribunal which had been constructed of earth in the Roman

fashion.

In stature she was very tall, in appearance most terrifying, in the glance of her eye most fierce,

and her voice was harsh; a great mass of the tawniest hair fell to her hips; around her neck was

a large golden necklace; and she wore a tunic of divers colors over which a thick mantle was

fastened with a brooch. This

was her invariable attire.

Having finished an appeal to her people of this general tenor, Boudicca led her army against

the Romans; for these chanced to be without a leader, inasmuch as Paulinus, their commander,

had gone on an expedition to Mona, an island near Britain.

(Dio Cassius 'Romaika' Epitome of Book LXII Chapter 7)>

According to Tacitus, the first target of Boudicca's army was the 'Colonia' at Camulodunum

(Colchester, Essex) — a colony of Legionary veterans and the "Romanized"

people who lived within the area. The colony was probably established in 49 AD by Publius Ostorius Scapula.

According to Tacitus, the first target of Boudicca's army was the 'Colonia' at Camulodunum

(Colchester, Essex) — a colony of Legionary veterans and the "Romanized"

people who lived within the area. The colony was probably established in 49 AD by Publius Ostorius Scapula.

The historian Tacitus describes the fall of Camulodunum:

The bitterest animosity was felt against the veterans; who, fresh from their settlement in the

colony of Camulodunum, were acting as though they had received a free gift of the entire country,

driving the natives from their homes, ejecting them from their lands — they styled them

"captives" and "slaves" — and abetted in their fury by the troops,

with their similar mode of life and their hopes of equal indulgence. More than this, the temple

raised to the deified Claudius continually met the view, like the citadel of an eternal tyranny;

while the priests, chosen for its [the temple's] service, were bound under the pretext of religion

to pour out their fortunes like water. Nor did there seem any great difficulty in the demolition

of a colony unprotected by fortifications — a point too little regarded by our commanders,

whose thoughts had run more on the agreeable than on the useful.

The statue of Victory at Camulodunum fell, for no apparent reason, with its back turned as if in

retreat from the enemy. Women, converted into maniacs by excitement, cried that destruction was at

hand and that alien cries had been heard in the invaders' senate-house: the theatre had rung with

shrieks, and in the estuary of the Thames had been seen a vision of the ruinedcolony. Again, that

the Ocean had appeared blood-red and that the ebbing tide had left behind it what looked to be

human corpses, were indications read by the Britons with hope and by the veterans with corresponding alarm.

However, as Suetonius was far away, they applied for help to

the procurator Catus Decianus. He sent not more than two hundred men, without their proper weapons:

in addition, there was a small body of troops in the town. Relying on the protection of the temple,

and hampered also by covert adherents of the rebellion who interfered with their plans, they neither

secured their position by fosse or rampart nor took steps, by removing the women and the aged, to

leave only able-bodied men in the place. They were as carelessly guarded as if the world was at

peace, when they were enveloped by a great barbarian host. All else was pillaged or fired in the

first onrush: only the temple, in which the troops had massed themselves, stood a two day siege, and

was then carried by storm.

(Tacitus 'Annals' Book XIV Chapters 31-33)

The only Legion available to immediately deal

with Boudicca's revolt was an element of Legio IX, commanded by Petilius Cerialis. The

Ninth probably numbered 5500 men, not including the auxiliaries attached to the Legion, which would have

been approximately another 5000. This meant Cerialis probably had a total 10,000 men under his command.

Evidence suggests that in addition to the vexillation fortress at Longthorpe in Cambridgeshire, there

are two other places in the area that also housed elements of Legio IX at this time. The first is the

vexillation fortress of Newton-on-Trent and the second at Lindum (>Lincoln).

Therefore, Cerialis would only have had immediate access to approximately a third of his Legion, or about 3,000 men.

The only Legion available to immediately deal

with Boudicca's revolt was an element of Legio IX, commanded by Petilius Cerialis. The

Ninth probably numbered 5500 men, not including the auxiliaries attached to the Legion, which would have

been approximately another 5000. This meant Cerialis probably had a total 10,000 men under his command.

Evidence suggests that in addition to the vexillation fortress at Longthorpe in Cambridgeshire, there

are two other places in the area that also housed elements of Legio IX at this time. The first is the

vexillation fortress of Newton-on-Trent and the second at Lindum (>Lincoln).

Therefore, Cerialis would only have had immediate access to approximately a third of his Legion, or about 3,000 men.

Leaving a small force to garrison the fortress at Longthorpe, the unit strength would have been 2,500 or less. He led his massively outnumbered troops in a desperate attempt to rapidly intercept Boudica's army (estimated at 100,000) before it attacked Londinium (London), the new administrative center of the province. As the Legion rushed to the aid of colonists, it was ambushed in marching column and suffered a catastrophic loss, according to Tacitus, of around 2000 men. This loss forced Cerialis to retreat with what was left of his cavalry contingent to the vexillation fortress at Longthorpe in Cambridgeshire, which is supported by archaeological evidence.

The fortress (Longthorpe I) is approximately 27 acres in area. It was excavated between 1967 and 1973 and shows that emergency defenses cut the camp to under half its size (Longthorpe II), to an area of 11 acres. The buildings within Longthorpe II show no evidence of being reorganized indicating these defenses were a panic measure by Cerialis fearing that Boudicca would follow and attack what was left of the contingent of Legio IX.

The Ninth suffered terribly in the revolt led by Boudicca (the battle was recorded by Tacitus as the Massacre of the Ninth). Roman historians could be very reticent in recording the facts about legions that had been disgraced, and officials weren't reluctant to cover up the fate of vanquished armies for sake of public morale. However, the unit's pride evidently remained intact because the Legion's commander Quintas Petillius Cerialis wasn't removed from his post, which suggests that he and his men behaved honorably.

As described by Tacitus:

Turning to meet Petilius Cerialis, commander of the Ninth Legion, who was arriving to the rescue,

the victorious Britons routed the Legion and slaughtered the infantry to a man: Cerialis with the cavalry

escaped to the camp and found shelter behind its fortifications.

(Tacitus 'Annals' Book XIV Chapters 31-33)

Reading Tacitus' account of the battle gives the impression the entire Legion was slaughtered, except for Cerialis and 120 cavalry. The impression is accurate if Tacitus' frame of reference is the small force of the Ninth led by Cerialis, but inaccurate in reference to the entire Legion. It is possible that Tacitus wrote his account to make the eventual defeat of Boudicca more auspicious.

The heroism and sacrifice of the Ninth was not in vain, however, because the delay of Boudicca's army allowed enough time for Governor Suetonius to gather his forces for a unified defense. Arriving at Londinium with an army of only approximately 10,000 men, composed of Legio XX (Valeria Victrix, Legio XIV Gemina (Maria Victrix) and any auxilia he could gather, he determined the city's defenses inadequate to make a stand against Boudicca's force of an estimated 230,000. Concluding he did not have the numbers to defend Londinium, Suetonius evacuated and abandoned it. It was burnt to the ground, as was Verulamium (St Albans). An estimated 70,000-80,000 people were killed in Boudicca's rebellion.

Dio writes:

Dio writes:

Those who were taken captive by the Britons were subjected to

every known form of outrage. The worst and most bestial atrocity committed by their captors was the

following. They hung up naked the noblest and most distinguished women and then cut off their

breasts and sewed them to their mouths, in order to make the victims appear to be eating them;

afterwards they impaled the women on sharp skewers run lengthwise through the entire body. All this

they did to the accompaniment of sacrifices, banquets, and wanton behavior, not only in all their

other sacred places, but particularly in the grove of Andate. This was their name for Victory, and

they regarded her with most exceptional reverence.

[Paullinus] was not willing to risk a conflict with the barbarians immediately, as he feared their

numbers and their desperation, but was inclined to postpone battle to a more convenient season. But

as he grew short of food and the barbarians pressed relentlessly upon him, he was compelled, contrary

to his judgment, to engage them.

(Dio Cassius (Xiphilinus) 'Romaika' Epitome of Book LXII Chapters 7-8)

Tacitus writes:

Tacitus writes:

Suetonius, on the other hand, with remarkable firmness, marched straight through the midst of the

enemy upon Londinium [London]; which, though not distinguished by the title of a colony, was

nonetheless a busy centre, chiefly through its crowd of merchants and stores. Once there, he felt

some doubt whether to choose it as a base of operations; but, on considering the fewness of his

troops and the sufficiently severe lesson which had been read to the rashness of Petilius

[Cerialis], he determined to save the country as a whole at the cost of one town. The laments

and tears of the inhabitants, as they implored his protection, found him inflexible: he gave

the signal for departure, and embodied in the column those capable of accompanying the march:

all who had been detained by the disabilities of sex, by the lassitude of age, or by local

attachment, fell into the hands of the enemy.

A similar catastrophe was reserved for the municipium

of Verulamium [St.Albans, Hertfordshire]; as the natives, with their delight in plunder

and their distaste for exertion, left the forts and garrison-posts on one side, and

made for the point which offered the richest material for the pillager and was unsafe

for a defending force. It is established that close upon seventy thousand Roman citizens

and allies fell in the places mentioned. For the enemy neither took captive nor sold

into captivity; there was none of the other commerce of war; he was hasty with slaughter

and the gibbet, with arson and the cross, as though his day of reckoning must come, but

only after he had snatched his revenge in the interval."

A similar catastrophe was reserved for the municipium

of Verulamium [St.Albans, Hertfordshire]; as the natives, with their delight in plunder

and their distaste for exertion, left the forts and garrison-posts on one side, and

made for the point which offered the richest material for the pillager and was unsafe

for a defending force. It is established that close upon seventy thousand Roman citizens

and allies fell in the places mentioned. For the enemy neither took captive nor sold

into captivity; there was none of the other commerce of war; he was hasty with slaughter

and the gibbet, with arson and the cross, as though his day of reckoning must come, but

only after he had snatched his revenge in the interval."

(Tacitus 'Annals' Book XIV Chapters 31-33)

Suetonius also sent a request for help to Poenius Postumus, commander of Legio II Augusta,

stationed near Exeter. Postumus refused to send aid or confront Boudicca's rebellious tribes, but instead

decided to remain within the Legion's fortress. Desperate to increase his number of troops, Suetonius also

sent a request to the remainder of the Ninth, who responded.

Suetonius also sent a request for help to Poenius Postumus, commander of Legio II Augusta,

stationed near Exeter. Postumus refused to send aid or confront Boudicca's rebellious tribes, but instead

decided to remain within the Legion's fortress. Desperate to increase his number of troops, Suetonius also

sent a request to the remainder of the Ninth, who responded.

left: Silver unit: weight 1.27 g, diameter 13 mm.

On the day of battle, Roman victory did not look likely. Boudicca had raised the banner of revolt in Norfolk and tens of thousands (by now an estimated 230,000) had joined her. In contrast the Roman army was reeling after a defeat of the Ninth Legion and Roman military governor, Suetonius Paullinus was left weak when the Legio II refused to march to meet the rebel forces.

Paulinus was outnumbered, his legionaries of 10,000 facing 230,000 howling tribesmen. Yet this caused his veterans, the remainder of the Ninth among them, little concern. Even with odds of ten to one against them, the Romans had faced far worse than that before. They knew that in the end, what won battles wasn't the weight of numbers, nor the chaotic onrush of vainglorious painted warriors, but years of weapons training, strict formation, and iron discipline. Sure enough, against the implacable shield wall of Roman legionaries, bristling with those short, squat, brutally effective stabbing swords, wave after wave of tribesmen broke and fell apart.

Tacitus wrote:

Tacitus wrote:

Suetonius had already the Fourteenth Legion,

with a detachment of the Twentieth and auxiliaries from the nearest stations, altogether

some ten thousand armed men, when he prepared to abandon delay and contest a pitched battle. He

chose a position approached by a narrow defile and secured in the rear by a wood, first satisfying

himself that there was no trace of an enemy except in his front, and that the plain there was devoid

of cover and allowed no suspicion of an ambuscade. The legionaries were posted in serried ranks, the

light-armed troops on either side, and the cavalry massed on the extreme wings. The British forces,

on the other hand, disposed in bands of foot and horse, were moving jubilantly in every direction.

They were in unprecedented numbers, and confidence ran so high that they brought even their wives to

witness the victory and installed them in wagons, which they had stationed just over the extreme

fringe of the plain."

(Tacitus 'Annals' Book XIV Chapter 34)

Dio's account:

Boudicca, at the head of an army of about 230,000 men,

rode in a chariot herself and assigned the others to their several stations. Paulinus could not

extend his line the whole length of hers, for, even if the men had been drawn up only one deep, they

would not have reached far enough, so inferior were they in numbers; nor, on the other hand, did he

dare join battle in a single compact force, for fear of being surrounded and cut to pieces. He

therefore separated his army into three divisions, in order to fight at several points at one and

the same time, and he made each of the divisions so strong that it could not easily be broken

through

(Dio Cassius 'Romaika' Epitome of Book LXII Chapter 8)

Tacitus Comments:

Boudicca, mounted in a chariot with her daughters before her,

rode up to clan after clan and delivered her protest: — It was customary, she knew, with Britons to

fight under female captaincy; but now she was avenging, not, as a queen of glorious ancestry, her

ravished realm and power, but, as a woman of the people, her liberty lost, her body tortured by the

lash, the tarnished honor of her daughters. Roman cupidity had progressed so far that not their very

persons, not age itself, nor maidenhood were left unpolluted. Yet Heaven was on the side of their

just revenge: one legion, which ventured battle, had perished; the rest were skulking in their

camps, or looking around them for a way of escape. They would never face even the din and roar of

those many thousands, far less their onslaught and their swords! — If they considered in their own

hearts the forces under arms and the motives of the war, on that field they must conquer or fall.

Such was the settled purpose of a woman — the men might live and be slaves!

Even Suetonius, in this critical moment, broke silence. In

spite of his reliance on the courage of the men, he still blended exhortations and entreaty: -

"They must treat with contempt the noise and empty menaces of the barbarians: in the ranks

opposite, more women than soldiers meet the eye. Un-warlike and unarmed, they would break

immediately, when, taught by so many defeats, they recognized once more the steel and the valor of

their conquerors. Even in a number of legions, it was but a few men who decided the fate of battles;

and it would be an additional glory that they, a handful of troops, were gathering the laurels of an

entire army. Only, keeping their order close, and, when their javelins were discharged, employing

shield-boss and sword, let them steadily pile up the dead and forget the thought of plunder: once

the victory was gained, all would be their own." Such was the ardor following the general's

words — with such alacrity had his seasoned troops, with the long experience of battle, prepared

themselves in a moment to hurl the >pilum [javelin] — that Suetonius,

without a doubt of the issue, gave the signal to engage.

At first, the legionaries stood motionless, keeping to the defile as a natural protection: then,

when the closer advance of the enemy had enabled them to exhaust their missiles with certitude of

aim, they dashed forward in a wedge-like formation. The auxiliaries charged in the same style;

and the cavalry, with lances extended, broke a way through any parties of resolute men whom they

encountered.

(Tacitus 'Annals' Book XIV Chapters 35-37)

Dio Continues:

...the armies approached each other, the barbarians with much shouting mingled with menacing

battle-songs, but the Romans silently and in order until

they came within a javelin's throw of the enemy. Then, while their foes were still advancing against

them at a walk, the Romans rushed forward at a signal and charged them at full speed, and when the

clash came, easily broke through the opposing ranks; but, as they were surrounded by the great

numbers of the enemy, they had to be fighting everywhere at once. Their struggle took many forms.

Light-armed troops exchanged missiles with light-armed, heavy-armed were opposed to heavy-armed,

cavalry clashed with cavalry, and against the chariots of the barbarians the Roman archers

contended. The barbarians would assail the Romans with a rush of their chariots, knocking them

helter-skelter, but, since they fought without breastplates, would themselves be repulsed by the

arrows. Horseman would overthrow foot-soldier and foot-soldier strike down horseman; a group of

Romans, forming in close order, would advance to meet the chariots, and others would be scattered by

them; a band of Britons would come to close quarters with the archers and rout them, while others

were content to dodge their shafts at a distance; and all this was going on not at one spot only,

but in all three divisions at once. They contended for a long time, both parties being animated by

the same zeal and daring. But finally, late in the day, the Romans prevailed ...

(Dio Cassius 'Romaika' Epitome of Book LXII Chapter 12)

Tacitus states:

The remainder [of the Britons] took to flight, although

escape was difficult, as the cordon of wagons had blocked the outlets. The troops gave no quarter

even to the women: the baggage animals themselves had been speared and added to the pile of bodies.

The glory won in the course of the day was remarkable, and equal to that of our older victories:

for, by some accounts, little less than eighty thousand Britons fell, at a cost of some four hundred

Romans killed and a not much greater number of wounded. Boudicca ended her days by poison; while

Poenius Postumus, camp-prefect of the Second Legion, informed of the exploits of the men of the

Fourteenth and Twentieth, and conscious that he had cheated his own corps of a share in the honors

and had violated the rules of the service by ignoring the orders of his commander, ran his sword

through his body.

(Tacitus 'Annals' Book XIV Chapter 37)

Dio continues:

Nevertheless, not a few [Britons] made their escape and

were preparing to fight again. In the meantime, however, Boudicca fell sick and died. The Britons

mourned her deeply and gave her a costly burial; but, feeling that now at last they were really

defeated, they scattered to their homes. So much for affairs in Britain.

(Dio Cassius 'Romaika' Epitome of Book LXII Chapter 12)

Tacitus writes:

Had not Paulinus on hearing of the outbreak in the province rendered prompt aid, Britain would

have been lost. By one successful engagement, he brought it back to its former obedience,

though many, troubled by the conscious guilt of rebellion and by particular dread of the legate,

still clung to their arms.

Tacitus concludes:

The whole army was now concentrated and kept 'subpellibus' (in tents —

literally "under hides"), with a view to finishing what was left of the campaign.

Its strength was increased by Caesar [i.e. Emperor Nero],

who sent over from Germany two thousand legionaries, eight cohorts of auxiliaries, and a thousand cavalry.

Their advent allowed the gaps in the Ninth Legion to be filled with regular troops; the allied foot and

horse were stationed in new winter quarters; and

the tribes which had shown themselves dubious or disaffected were harried with fire and sword.

Nothing, however, pressed so hard as famine on an enemy who, careless about the sowing of his crops,

had diverted all ages of the population to military purposes, while marking out our supplies for his

own property. In addition, the fierce-tempered clans inclined the more slowly to peace because

Julius Classicianus, who had been sent in succession to Catus and was not on good terms

with Suetonius, was hampering the public welfare by his private animosities, and had circulated a

report that it would be well to wait for a new legate [i.e. governor]; who, lacking the bitterness

of an enemy and the arrogance of a conqueror, would show consideration to those who surrendered. At

the same time, he reported to Rome that no cessation of fighting need be expected until the

supersession of Suetonius, the failures of whom he referred to his own perversity, his successes to

the kindness of fortune.

Accordingly Polyclitus, one of the [imperial] freedmen, was

sent to inspect the state of Britain, Nero cherishing high hopes that, through his influence, not

only might a reconciliation be effected between the legate and the procurator, but the rebellious

temper of the natives be brought to acquiesce in peace. Polyclitus, in fact, whose immense train had

been an incubus to Italy and Gaul, did not fail, when once he had crossed the seas, to render his

march a terror even to Roman soldiers. To the enemy, on the other hand, he was a subject of

derision: with them, the fire of freedom was not yet quenched; they had still to make acquaintance

with the power of freedmen; and they wondered that a general and an army who had accounted for such

a war should obey a troop of slaves. None the less, everything was reported to the emperor in a more

favorable light. Suetonius was retained at the head of affairs; but, when later on he lost a few

ships on the beach, and the crews with them, he was ordered, under pretence that the war was still

in being, to transfer his army to Petronius Turpilianus, who by now had laid down his consulate. The

new-comer abstained from provoking the enemy, was not challenged himself, and conferred on this

spiritless inaction the honorable name of peace."

(Tacitus 'Annals' Book XIV Chapters 38-39)

Endgame

It is clear the sacrifice of the Ninth gave Suetonius time to regroup his forces in the

West Midlands,

and despite being heavily outnumbered, defeated the Britons in the Battle of Watling Street. The crisis caused

the emperor Nero to consider withdrawing all

Roman forces from the island, but Suetonius' eventual victory over Boudicca secured Roman control of the

province. Boudica then killed herself so she would not be captured, or fell ill and died; Tacitus and Dio

differ. Disgraced, Polineus Postumus, commander of Legio II Augusta, [rightly] committed suicide.

It is clear the sacrifice of the Ninth gave Suetonius time to regroup his forces in the

West Midlands,

and despite being heavily outnumbered, defeated the Britons in the Battle of Watling Street. The crisis caused

the emperor Nero to consider withdrawing all

Roman forces from the island, but Suetonius' eventual victory over Boudicca secured Roman control of the

province. Boudica then killed herself so she would not be captured, or fell ill and died; Tacitus and Dio

differ. Disgraced, Polineus Postumus, commander of Legio II Augusta, [rightly] committed suicide.

According to Tacitus, after the revolt, Legio IX was restored to strength with reinforcements from the German provinces in 65 AD and moved from Longthorpe and Newton-on-Trent to two new bases; the first, a new fortress at Lindum (Lincoln) and the second, at Rossington or Osmanthorpe. Both have been identified as pre-Flavian vexillation fortresses. The new fortress at Lincoln is presumed to have been built by Legio IX because of the number of burials of soldiers of the Ninth found below the fortress. Unfortunately, there are no monumental inscriptions saying Legio IX built the new fortress, but it may be inferred by the presence of these burials.

The Brigantes and Discord in the Empire

The next problem Legio IX was probably forced to deal with was the feud in Brigantia between Cartimandua and her ex-husband Venutius. Trouble in Brigantia had been brewing since 52 AD when the Queen, Cartimandua, handed over the fugitive leader Caratacus, who had fled to Brigantia in the hope of evading the Romans. It seems that the Queen had been pro-Roman since they had been invaded, although her husband Venutius seemed more cautious about the Romans. Evidence suggests that Cartimandua had grown fond of the luxuries of Rome, such as fine glass wares and wines, much to the displeasure of her husband, Venutius. She must have been loyal to the Romans, because in 60 AD when Boudicca revolted, the Brigantes did not rise in support of her.

The fragile peace found in Brigantia, may also have been the reason the other half of Legio IX did not come to the aid of Cerialis when he fought Queen Boudicca. Since the legion was based around the edge of Brigantia, they were probably expecting trouble. The peace with Brigantia only lasted until 69 AD, when the Queen divorced her husband, Venutius, taking her armor-bearer, Vellocatus, as her lover.

The

years 68-70 was a time of turmoil within the empire as four would-be Roman Emperors struggled for power.

Making matters worse, each legion in Britain, as well as throughout the Empire, supported a different

candidate for emperor; Nero was forced to commit suicide (June 68)

and was succeeded by the old senator Galba; who was murdered by soldiers

(January 69) of Otho, who then, in turn, commited suicide

(April 16, 69) after his army was defeated by Vitellius' army. Vitellius tried

to abdicate, but the Praetorian Guard refused to allow him to carry out the agreement, and forced him

to return to the palace. After a bloody battle for Rome, Vitellius was eventually dragged out of a

hiding-place (according to Tacitus a door-keeper's lodge), driven to the fatal

Gemonian stairs, and there struck down by Vespasian's supporters. The Vespasian

ascended to the purple.

The

years 68-70 was a time of turmoil within the empire as four would-be Roman Emperors struggled for power.

Making matters worse, each legion in Britain, as well as throughout the Empire, supported a different

candidate for emperor; Nero was forced to commit suicide (June 68)

and was succeeded by the old senator Galba; who was murdered by soldiers

(January 69) of Otho, who then, in turn, commited suicide

(April 16, 69) after his army was defeated by Vitellius' army. Vitellius tried

to abdicate, but the Praetorian Guard refused to allow him to carry out the agreement, and forced him

to return to the palace. After a bloody battle for Rome, Vitellius was eventually dragged out of a

hiding-place (according to Tacitus a door-keeper's lodge), driven to the fatal

Gemonian stairs, and there struck down by Vespasian's supporters. The Vespasian

ascended to the purple.

It is possible that elements of Legio IX were taken by Cerialis from Britain to help him support one of the candidates. Therefore, Cartimandua could no longer be supported by the Roman army, which provided an opportunity for her ex-husband, Venutius, to take control of Brigantia. The chaos within the Roman army is indicated by Tacitus when he writes that Cartimandua was rescued, not by legionnaires, but a force of auxiliaries. (Tacitus, HIST 111, 45)

Cerialis returned to Britain after participating in an important campaign in the

Rhineland in 70 AD against the rebellious Batavians. Upon his return, he took personal command of IX Hispana

in 78 AD. Legio IX was moved to Eburacum (York) where it replaced

II Adiutrix to guard the northern fringes of the Empire. This is the

last recorded and datable action of the Legion based on legionary stamps found on tiles at the

imperial fortress at Eburacum (York). There is also some evidence the legion

was likely to have been based at Malton.

Cerialis returned to Britain after participating in an important campaign in the

Rhineland in 70 AD against the rebellious Batavians. Upon his return, he took personal command of IX Hispana

in 78 AD. Legio IX was moved to Eburacum (York) where it replaced

II Adiutrix to guard the northern fringes of the Empire. This is the

last recorded and datable action of the Legion based on legionary stamps found on tiles at the

imperial fortress at Eburacum (York). There is also some evidence the legion

was likely to have been based at Malton.

Brigantia and Venutius were about to feel the power of Rome when Gnaeus Julius Agricola, commander of XX Valeria Victrix and Petilius Cerialis, commander of Legio IX, moved north. It is likely that Venutius met the might of Rome at Stanwick, the supposed center of Brigantia in 72 AD. Together, Legions IX and XX crushed Venutius. The historical record does not tell us what happened to Venutius, but in all likelihood, he did not survive.

After The Brigantes

After the defeat of Venutius it is likely that Legio IX was used to continue to try and pacify the Brigantes. Under the new governor, Julius Frontinus (73-77 AD), the legion embarked on the consolidation of the newly conquered territory and would have started building a new permanent base at York, which could house the whole legion in comfort.

It was not until the governorship of Agricola in 78 AD the rest of Brigantia was subjugated, possibly by Legio IX. Agricola's first task was to sort out the remnants of trouble in Brigantia. The natural choice in making this advance northwards would have been Legio IX, as it must have been familiar with the surrounding area as a result of being based at York.

Tacitus tells us a great deal about the campaigns of Agricola in Britain, but he omits which legions were involved and where they were used. The dates of all of Agricola's campaigns are questioned fiercely by historians, so for our purposes, two possible years will be given in each case.

Agricola started his first campaign in 78/79 and by the end of the first season, he is thought to have reached as far north as the Bowes-Tyne line, later to become Hadrian's Wall. Tacitus states that it was a two-pronged attack, moving up either side of the Pennines. It seems probable that Legio IX advanced up the eastern side, possibly as far as Corbridge, where Agricola established a supply area.

In 79/80, Agricola again advanced and it would seem likely that Legio IX went with him. It is also possible at this stage, that Legio IX was combined with another legion for this advance — however, which other legion is not known. By the end of the 79/80 campaign, it is possible that Legio IX was returned to York. No further mention of Legio IX occurs until the campaigns of 82/83.

In 82/83, Agricola crossed the Forth-Clyde line and Legio IX was involved; Tacitus tells us the Ninth was attacked at night in their camp and "defeated":

Tacitus: 'As soon as the enemy got to know of this they suddenly

changed their plans and massed for a night attack on Legio IX.'

(AGRICOLA, 26)

Tacitus describes Legio IX as "Maxime invalida, " (weakest of all). A possible reason for this description may be due to the fact that as many as 1,000 men of the Ninth and other legions were removed from Britain, which seems to have caused some difficulties for Agricola's campaign by not giving him sufficient strength for a successful campaign. In 83 a detachment of IX Hispana fought against the Chatti, a Germanic tribe near Mainz in Germania Superior, an inscription records the fact that a senior Tribune of Legio IX won decorations during the campaign, which possibly documents the Ninth's participation. It is also thought that a subunit of the Ninth took part in Trajan's invasion of Dacia nearly the same time, but this is not proven.

Regardless,

the defeat of Legio IX would have had to have been on a large scale for it to be worthy of a note by Tacitus.

However, it could have been just another ploy to make Agricola look good when he won the day. It is not known

where this attack on Legio IX took place, but it has been suggested that a marching camp sited near Dornock

may fit Tacitus's story; being 33 acres — it could have easily accommodated a legion under tents, which

was said to be "subpellibus," literally "under hides."

Regardless,

the defeat of Legio IX would have had to have been on a large scale for it to be worthy of a note by Tacitus.

However, it could have been just another ploy to make Agricola look good when he won the day. It is not known

where this attack on Legio IX took place, but it has been suggested that a marching camp sited near Dornock

may fit Tacitus's story; being 33 acres — it could have easily accommodated a legion under tents, which

was said to be "subpellibus," literally "under hides."

It is not known what happened to Legio IX after it was attacked and depending on its condition, it would either have continued to campaign with Agricola or been withdrawn, either to Inchtuthil or back to York. It would seem likely that, because he was short of troops, Agricola retained Legio IX in the field until the end of the campaign.

After Agricola was recalled from Britain his conquests in Scotland were let go, and the army retreated back to the Bowes-Tyne line, with Legio IX possibly returning to York. Agricola was a prolific fort builder and it may be possible that many of the forts built in his name were constructed by Legio IX. From the evidence of these forts it's possible to plot Agricola's campaigns.

A Time of Building

After its move back to York, Legio IX probably settled into a more mundane state of existence, patrolling the local area and bringing the unit back up to strength, after the mauling it received in Scotland. Between December 107 and December 108, the legion erected a monument with an inscription dedicated to the Emperor Trajan over the southeastern gate of a rebuilt stone fortress. This inscription is only one of the ways that Legio IX is known to have built York; there have been three other inscriptions found and attributed to the men of Legio IX, including a particularly fine one commemorating the standard-bearer Lucius Duccius Rufinius. Legio IX may have used this period to redevelop the fortress at York replacing many of the buildings.

The evidence for Legio IX rebuilding in stone also comes from stamped tiles embossed with the title LEG IX HISP. The inscription dedicated to Trajan, is the last dated reference to Legio IX being present in Britain, but it might not mean the legion was absent from the province after that date. It would seem more than likely that the Ninth was moved from York in about 120 AD when Legio VI Victrix appears to have moved into the fortress.

Onwards

It is highly likely that Legio IX was moved to Carlisle, which was probably established by Petilius Cerialis in 71 AD, after it vacated the fortress at York. Evidence of the Legion's presence at Carlisle is in the form of stamped tiles embossed with LEG VIIII HISP. The tiles were being produced five miles southeast of Carlisle at the recently identified legionary tile depot at Scalesceugh. A magnetometer survey of the site has identified 24 kilns that were probably used to produce enough tiles to build Legio IX's new fortress at Carlisle.

Legio IX started stamping the tiles from the kilns at Scalesceugh with the title LEG VIIII HISP, since no tiles bearing this stamp have been found yet in York, it is, therefore, assumed that the Legion had several centers of tile production. It should also be noted that stamped tiles bearing the title LEG VIIII HISP have also been found at Stanwix; so the Legion may have again been deployed in two places in the north. Until further work is done on these two sites it will be difficult to prove that the Ninth was based there. Inscriptions from the fort at Stanwix suggest that it was the home of the Ala Petriana; if this is correct then the Ninth may have built this fort.

If all of the Ninth did move to Carlisle, there must have been a reason for the move, and one may

assume that the reason was that it was used to help build the western end of Hadrian's Wall. As this half

of the wall was built in turf, the inscriptions would have been made of wood, which is probably why they do

not survive to either prove or disprove the Ninth's presence. Regardless, it is unlikely that LEGIO IX

stayed very long in Carlisle or Stanwix. The archaeological record shows they moved from Britain to Nijmegen

in Holland to replace Legio X Gemina, where tiles and grave

markers have been found bearing Legio IX's stamp.

If all of the Ninth did move to Carlisle, there must have been a reason for the move, and one may

assume that the reason was that it was used to help build the western end of Hadrian's Wall. As this half

of the wall was built in turf, the inscriptions would have been made of wood, which is probably why they do

not survive to either prove or disprove the Ninth's presence. Regardless, it is unlikely that LEGIO IX

stayed very long in Carlisle or Stanwix. The archaeological record shows they moved from Britain to Nijmegen

in Holland to replace Legio X Gemina, where tiles and grave

markers have been found bearing Legio IX's stamp.

The history of Legio IX in Britain and the campaigns in which it took part are by no means certain due to so little archaeological and written evidence. But fortunately, there is enough evidence to be certain of several things.

- Several members of Legio IX are known to have been buried in Britain, at both Lincoln and York.

- Legio IX built a gate in York dedicated to Emperor Trajan.

- Legio IX also stamped its tiles with the title LEG IX HISP or LEG VIIII HISP, at several locations around the north of Britain.

- There are only two written accounts of campaigns that Legio IX is known to have taken part during the Roman occupation, the first was the Boudiccan revolt and the second was with Agricola during his campaigns in Scotland. It must be remembered that the picture of Roman military occupation in Britain may be far more complicated than has been assumed by historians.

- As more archaeological discoveries are made, the evidence for Legio IX being present in Britain may increase, and eventually it could be possible to chart their campaigns with a greater deal of accuracy.

- We have used the evidence available for Legio IX to try to fit it into the historically known facts about the Roman campaigns in Britain. However, much is still open for speculation and interpretation and, due to the scope of this subject there may be many alternative suggestions to when and where Legio IX campaigned in Britain.

What Happened to the Ninth?

Certainly it's true that Roman historians could be very reticent in recording the facts about legions that had been disgraced, and officials weren't adverse to covering up as best as possible the fate of vanquished legions for the purpose of preserving public morale. Legio IX Hispana may have even been crushed so completely and so mercilessly that Hadrian deemed that telling the true story of its fate should be constitutionally banned. But more likely, the Ninth was just moved on again, as it had been so many times before.

Last Mention in Britain

The last recorded, datable activity of Legio IX in Britain was in 108/109, when it built a stone fortress at York. What happened next is unclear. Several scholars have argued that it was defeated and annihilated by the Picts, perhaps in 117/118, and that this caused the emperor Hadrian to build the famous wall in northern England (this is the assumption of the famous novel by Rosemary Sutcliff, The Eagle of the Ninth, 1954.)

To the Continent

However, more recent research has shown that a subunit of Legio IX

was at Nijmegen in Germania Inferior, for a brief period after 121. At the same time VI Victrix

was transferred from Germania Inferior to Britain. Perhaps they traded places with the

Ninth? The main force wasn't present though, and since detachments had fought separately in Germania before

— for instance near Mainz against the Chatti in 83 AD — this arguably could have been the same detachment.

However, more recent research has shown that a subunit of Legio IX

was at Nijmegen in Germania Inferior, for a brief period after 121. At the same time VI Victrix

was transferred from Germania Inferior to Britain. Perhaps they traded places with the

Ninth? The main force wasn't present though, and since detachments had fought separately in Germania before

— for instance near Mainz against the Chatti in 83 AD — this arguably could have been the same detachment.

The fact that we know the names of several high officers of Legio IX who cannot have served earlier than 122 (>i.e., Lucius Aemilius Karus, governor of Arabia in 142/143) is indication that we can safely assume that the core of the unit was still operating in the reign of Hadrian (117-138 AD). After this, the legion disappears from our sources. Some speculate the Ninth may have even assisted in building segments of Hadrian's Wall, although this seems fanciful.

The one certainty is that Legio IX Hispana did not exist by the reign of Marcus Aurelius (>161-180) because a listing of active legions by that Emperor makes no mention of the Ninth, which means this means that it was destroyed before or during his reign. It could have been annihilated in the Province of Judaea during the Bar Kochba Revolt of Simon ben Kosiba (132-136) in Cappadocia in 161, during a revolt on the Danube in 162, or at some stage in the long running battle between Rome and the Parthian Empire.

Whatever the true story is about the demise of Legio IX Hispana, the popular fascination with its perceived mysterious and macabre fate will probably never be eclipsed.